State-Transition Diagram

State-Transition Diagram explained

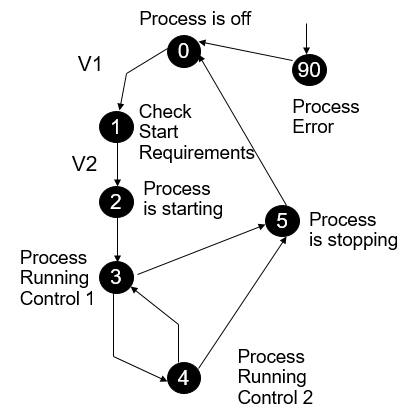

A State-Transition Diagram (STD) is a powerful tool frequently utilized in control engineering. It provides a comprehensive overview of all the possible states a system can undergo and illustrates the links between them using transition lines. These lines serve as visual cues that demonstrate how one state can progress into the next and also highlight the transition requirements needed to move from one state to another. In summary, STDs help to simplify the complex system into a visual representation that allows for better analysis and understanding of the system’s behavior. Figure 1 illustrates an example of an STD.

An STD is not just a visual tool; it can track different states and send signals to control a program. It works within the same constraints as a step program, but with inherent rules that set it apart.

The requirements for a STD are as follows:

-

Only one state can be active at a time.

-

Only one transition can occur during a run-cycle.

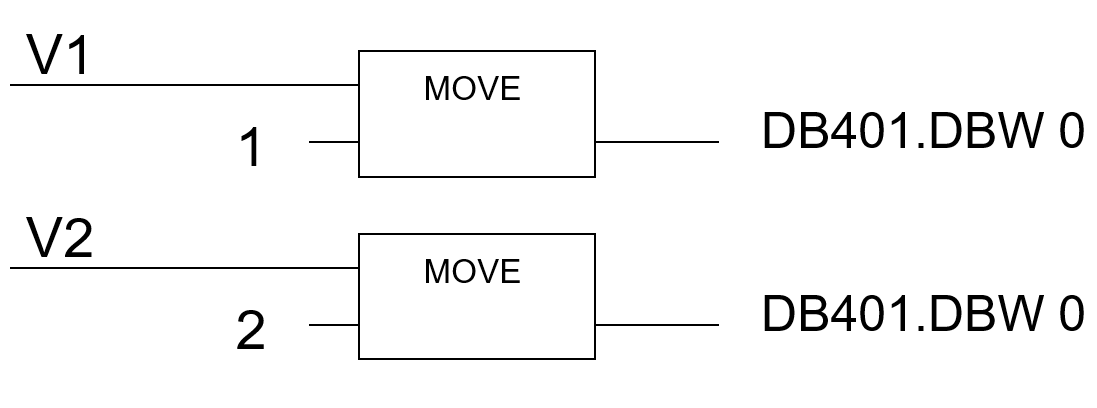

The first requirement of an STD specifies that only one state can be active. To achieve this, the STD uses an address with a pointer. The address refers to all possible states, and stores a variable that functions as a pointer. This variable is typically represented by an integer or bit number, and it points to the currently active state. To update this variable, multiple "MOVE" blocks can be used, each with its own set of requirements for a state transition. If these requirements are met, the MOVE block triggers a change in the variable, which in turn changes the state that the address points to. The example given in the Figure 2 shows a graphical representation of a state transition diagram, with arrows indicating the transitions between different states, and MOVE blocks indicating the conditions that trigger these transitions.

The second requirement of an STD specifies that only one transition can happen during a run-cycle. To meet this requirement, the conditions for a state change must be adjusted. The transition requirements must include that "the state before this is active" to ensure that the program moves through each state in a step-by-step manner, without skipping any steps. It is important to keep in mind that the variable pointer is being overwritten, so when a new state becomes active, the previous state is replaced and becomes inactive.

Why use an STD?

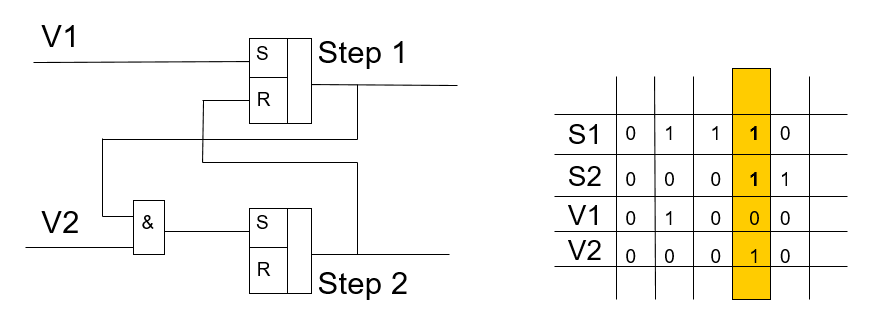

Previously, step programs were commonly used. However, these programs have inherent flaws that create problems for control engineers. The most significant issues that still occur in step programs are skipping steps and undesired behavior resulting from multiple steps being active simultaneously. Both problems originate from the setup of a step program. An example is provided below.

The truth table above shows that the step program can have moments where multiple states are active. This can cause controlled elements to receive conflicting or incorrect control signals, which can ultimately impact the entire program. Additionally, these signals can cause future requirements to become true, resulting in the step program skipping to a step that should not be executed yet. These problems are so common that control engineers using step programs often have to reset them and rerun all steps to correct errors. To address these issues, STDs were developed to provide a solution.

In addition to solving these problems, another reason to use STDs is their scalability. Step programs require meticulous planning, as adding new steps in the future can cause the program to grow exponentially in complexity. In contrast, STDs can be expanded easily by adding new states and the required transition lines. This typically results in smaller, more readable programs compared to step programs.

To learn how to create STDs click here.